Jim McDowell’s Hamatsa: The Enigma of Cannibalism on the Pacific Northwest Coast (1997), first shown to me by Steve Calvert in summer 2015, was an important inspiration for the unfolding of The Skullcracker project. The Hamatsa are a secret society of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples of coastal British Columbia, made famous in ethnographic circles by Franz Boas and George Hunt at the turn of the last century, and brought to a wider international public at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893 (where Boas presented a living-tableau of Hamatsa dancers), and by Edward S. Curtis in his early cinematic ethno-fiction In the Land of the Headhunters (1914). Steve was aware of a book I had recently written about Haiti as depicted through the optic of ‘Voodoo Horror’: Undead Uprising. Cannibalism’s association with Vodou after the Haitian Revolution ultimately gave rise to the contemporary, flesh-eating zombie of popular culture. Like the Bizango secret society in Haiti – whose members are reputed to be capable of taking animal form and of making zombis – the Hamatsa seem to have been regarded from a similar colonial perspective, which often misinterpreted the ritual practices of the people they hoped to control and exploit in light of European prejudices and fantasies.

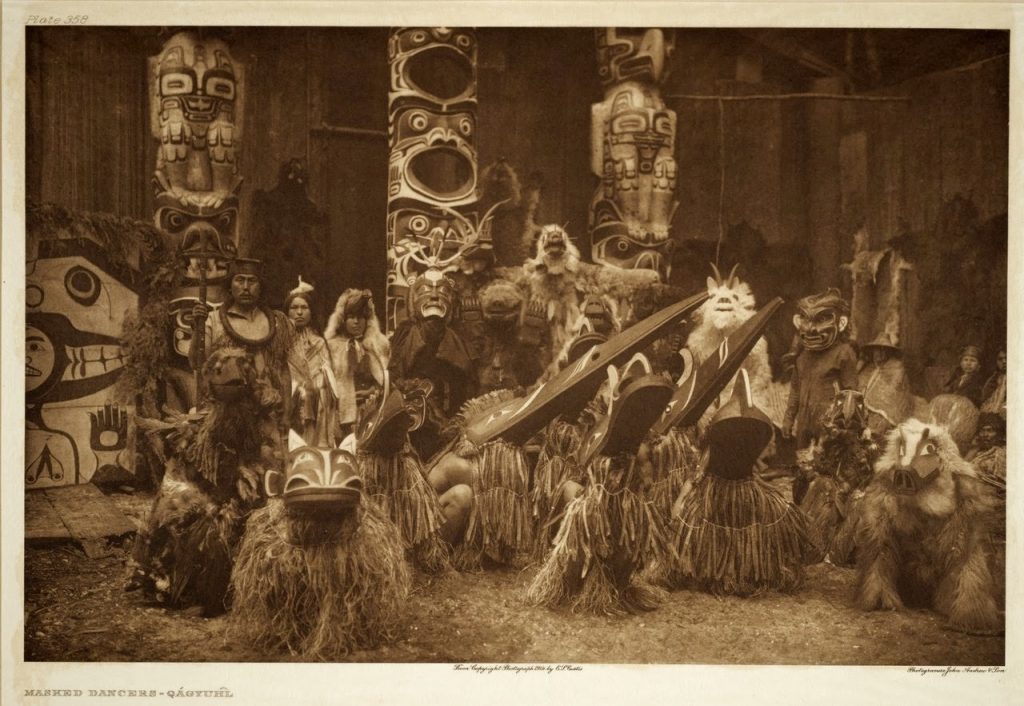

Jim McDowell’s Hamatsa: The Enigma of Cannibalism on the Pacific Northwest Coast (1997), first shown to me by Steve Calvert in summer 2015, was an important inspiration for the unfolding of The Skullcracker project. The Hamatsa are a secret society of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples of coastal British Columbia, made famous in ethnographic circles by Franz Boas and George Hunt at the turn of the last century, and brought to a wider international public at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893 (where Boas presented a living-tableau of Hamatsa dancers), and by Edward S. Curtis in his early cinematic ethno-fiction In the Land of the Headhunters (1914). Steve was aware of a book I had recently written about Haiti as depicted through the optic of ‘Voodoo Horror’: Undead Uprising. Cannibalism’s association with Vodou after the Haitian Revolution ultimately gave rise to the contemporary, flesh-eating zombie of popular culture. Like the Bizango secret society in Haiti – whose members are reputed to be capable of taking animal form and of making zombis – the Hamatsa seem to have been regarded from a similar colonial perspective, which often misinterpreted the ritual practices of the people they hoped to control and exploit in light of European prejudices and fantasies.

Central to the mythology of the Hamatsa are three giant man-eating birds, companions of the giant ‘Man Eater at the North End of the World’, Baxbaxwalanuksiwe, whose body is covered in gaping mouths. That a human-eating creature can be conceived of as a cannibal is central to the Skullcracker project, which proposes that having one’s skull cracked and brain eaten by a fellow creature is an apt metaphor for the violently interwoven and ritually theatricalized processes of colonization/decolonization that the Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro has called Cannibal Metaphysics.

One of the principle tasks of The Skullcracker project is to reflect on Viveiros de Castro’s advocacy for the “permanent decolonization of thought” in the context of the cultural politics of contemporary British Columbia, and particularly within the fields of contemporary art and indigenous resurgence there since the 1970’s. How might the great cannibal birds of Hamatsa legend and the traditional ceremonial culture of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples guide us in this path?