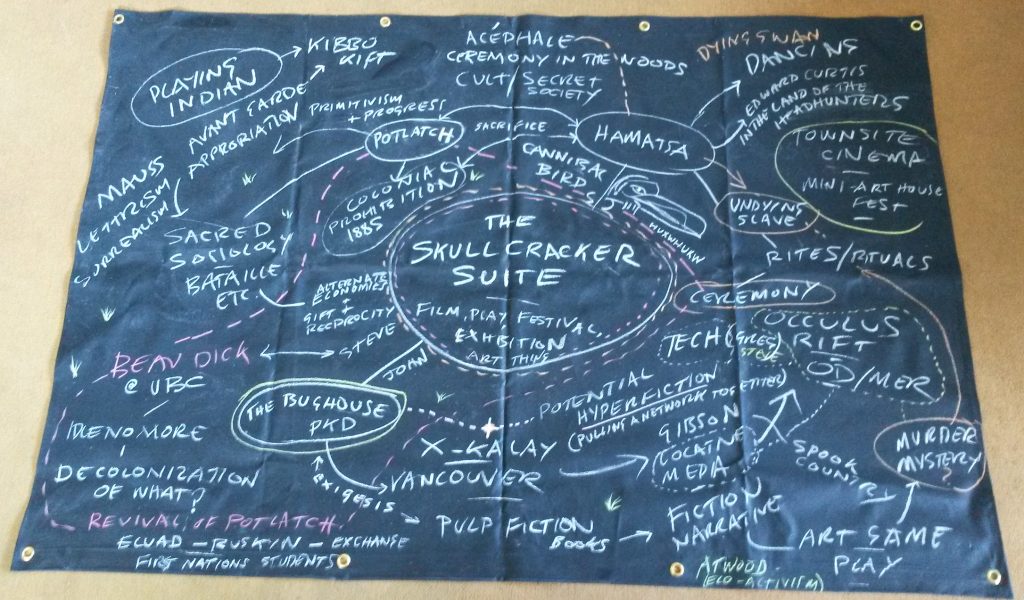

The Skullcracker Suite was conceived during a visit with my friend Steve Calvert in Powell River in the summer of 2015. Steve, whom I had not seen since 2002, had been living for several years in Alert Bay, home of the ‘Namgis First Nation, documenting their potlatch ceremonies, and accompanying the Kwakwaka’wakw artist, hereditary chief, and indigenous activist Beau Dick* on his journey to the legislature of British Columbia to symbolically break a traditional copper and call The Crown by its true name, Raven.

During our few days together Steve told me many stories about his time in Alert Bay, about the genocidal policies of the Canadian government, still at work today in regions far from the metropolitan centres, and the politics of indigenous resurgence associated with Idle No More. He also told us about the vibrant culture of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples of the region, their legends, theatre, music and the incredible stage-craft of the ceremonies he had attended.

Back in 2000 Steve had audited a class I taught at Emily Carr College of Art and Design called The Sacred Revolution: Ethnographic Surrealism and the Sociology of the Sacred. The course was based on the writings of the French Surrealist philosopher Georges Bataille, whose book The Accursed Share contains an important section on the potlatch economy. Bataille described the potlatch as a gift of rivalry between tribal chiefs, leading to ever greater destructions of material wealth. Traditional modes of non-productive expenditure like the potlatch represented for Bataille a form of socio-economic organization that maintained an intimate and primordial connection between art, community and the sacred. As such it seemed to him to offer a model counter-point to the individualistic, calculating and profane logics of modern capitalist economies.

Back in 2000 Steve had audited a class I taught at Emily Carr College of Art and Design called The Sacred Revolution: Ethnographic Surrealism and the Sociology of the Sacred. The course was based on the writings of the French Surrealist philosopher Georges Bataille, whose book The Accursed Share contains an important section on the potlatch economy. Bataille described the potlatch as a gift of rivalry between tribal chiefs, leading to ever greater destructions of material wealth. Traditional modes of non-productive expenditure like the potlatch represented for Bataille a form of socio-economic organization that maintained an intimate and primordial connection between art, community and the sacred. As such it seemed to him to offer a model counter-point to the individualistic, calculating and profane logics of modern capitalist economies.

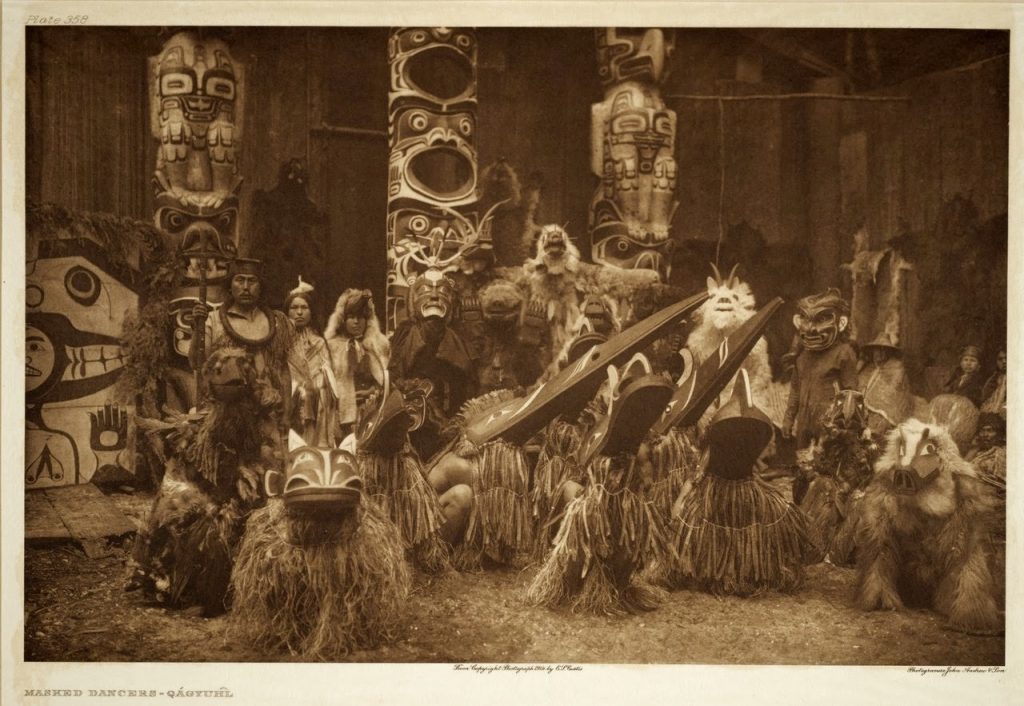

Many of Steve’s stories had to do with the Hamatsa, a secret society, several members of which Steve had become friends with during his time in Alert Bay. One story, told to Steve by Beau, was particularly striking, reminding Steve of the secret society Bataille himself had founded in the 1930’s, Acéphale, which would meet in the woods outside Paris to perform mysterious sacrificial ceremonies at the foot of a sacred tree. In Beau’s story a young man who had strayed from his village is captured by a war party from a rival tribe and forced to become a slave. Eventually, having upset the chief in some way, it was decided that he would be sacrificed during the next winter dance ceremony. However, despite being decapitated, thrown in the fire, and taken out into the sea to be drowned, the slave refused to die. Eventually he is admitted into the tribe as one of its own. Steve had witnessed a performance of this story during Beau’s potlatch. After the slave had been symbolically stabbed three times, his decapitated head was made to roll dramatically across the floor of the Alert Bay big house before being magically reconnected with its owner. Although the technical virtuosity of the Kwakwaka’wakw ceremonial dances have been well-known to ethnographers and anthropologists since Franz Boas, such stories were new to me.

I was captivated by the thought of an artistic work combining the kind of Grand Guignol stage craft described by Steve, ritual dance, costume and music, designed to tell a contemporary story about the ongoing legacy of colonialism in the region and its cannibalistic, all-consuming character.

One of the most emblematic dances of the Hamatsa involves three giant cannibal birds who are the consorts of Baxbaxwalanuksiwe, ‘Man Eater at the North End of the World’. One of these birds, Huxhukw, is a giant crane, who cracks the skulls of men to eat their brains. The idea of a giant skull-cracking bird, eating human brains in the primordial forests of Northern Canada seemed like an image from an eco-horror movie. It also brought to mind other ceremonies and rites associated with deep winter, still alive in Europe and its colonies, like Mummers plays and the Krampus traditions in Alpine Europe. It also recalled that famous Christmas tale of toys coming to life and fighting mouse armies: E.T.A. Hoffman’s The Nutcracker and Mouse King, famously made into a ballet by Tchaikovsky in 1892.

In the UK the word nut is slang for head. To be “cracked in the head” or “nutty” means being crazy. What kind of crack pots and nut jobs would try to bring together the traditions of Kwakwaka’wakw winter dance ceremonies, inter-species and inter-planetary science-fiction, and the multinatural perspectivism of Amerindian philosophy with a mystical theatre of ritual sacrifice and subjective transformation? How would such a project work? What would it look like? And what would it do? These are the kinds of questions that The Skullcracker Suite was created to address.

* Beau’s untimely passing in March 2017 was not only an immense loss to his family, friends, colleagues and community, but to the wider artistic, environmentalist and activist culture in BC as a whole. He seems to have had a powerful influence on everyone came to know him, as this commemorative video made by his students shows.

Here’s a telling epithet for Beau by himself, spoken shortly after he performed the first copper-breaking ceremony in Victoria, from David Shebib and Davis Arthur Johnston’s mini-documentary on Beau’s copper-breakin protest ‘What Now?‘:

“All we can do at this point is create awareness. We’re in a predicament. We can’t be in denial. Our values have to shift. In our case, from a First Nations’ perspective, we have to get back to the old ways, to live in harmony and be in balance with nature, and Ma’ya’xala, the creator. In saying that, we have to get rid of the old ways in order to go back to the old ways, because we’ve been subdued for so long, we’re quite accustomed to it. If there’s any hope for us, and the rest of mankind, we have to shake those chains off and be able to grow. And young people have fresh young minds and they have abilities that us older people don’t. And as we pass the torch forward now it’s up to them to take on the responsibility as they grow up. This is their world too. Don’t be like us. Be better than us. That’s the only voice that I can send out to young people.”

Beau Dick (1955 -2017)